Dairy X Beef Summit: New scours, starter intake and calf comfort research for beef-on-dairy calves

Research highlights a 21-lb. weaning weight penalty tied to pre-weaning diarrhea in beef-on-dairy calves

Diarrhea remains the single biggest threat to calf survival and performance in the first weeks of life, and research data suggest beef-on-dairy calves may be especially vulnerable to its long-term impact.

That was one of the central messages delivered by Dr. Mike Ballou, professor and chair of the Department of Veterinary Sciences at Texas Tech University, during a presentation on pre-weaning calf performance and gut health at the Four Star Veterinary Service Beef on Dairy Summit held in Celina, Ohio in early December 2025.

Drawing on research conducted at Texas Tech as well as his own practical experience owning and managing calf ranches in the Midwest and Southwest, Ballou outlined how early-life disease, nutrition and environment interact to shape lifetime performance particularly for beef-on-dairy calves.

“Improving the performance in the hutch sets the stage for improved post-weaning performance and health,” Ballou said. “Nutrition plays a role; health plays a role; environment plays a role.”

While those principles are familiar, Ballou emphasized that putting numbers behind them reveals important differences between beef-on-dairy calves and traditional Holstein calves – differences that carry significant implications for calf raisers, backgrounders and feedlot operators increasingly reliant on beef-on-dairy genetics.

Scours still drives early calf mortality

Ballou began by revisiting one of the most persistent challenges in calf rearing: neonatal diarrhea.

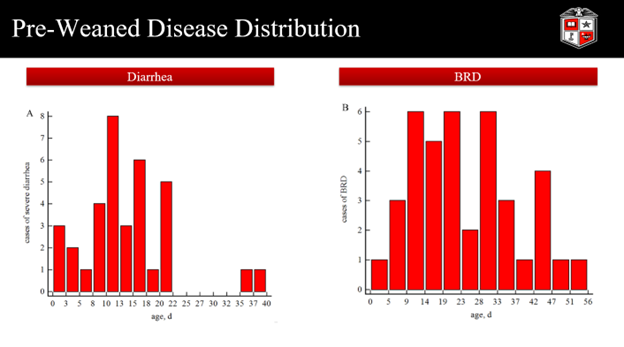

Using data from a Texas Tech study involving approximately 250 calves including half Holstein steers and half Holstein-Angus crosses, Ballou described how disease incidence and outcomes were tracked through the first 56 days of life. All calves had ad libitum access to water and starter, were fed a standard milk replacer program of three quarts twice daily and were monitored twice daily for signs of scours and bovine respiratory disease (BRD).

“What you’re going to see is pretty typical curves that you would see in most facilities,” Ballou said. “Most of the scours are occurring in the first 21 days of life.”

The consequences, however, were anything but routine. Survival analysis revealed that calves experiencing scours were dramatically more likely to die before weaning.

“At least in my Texas Tech facility, scours is still the main cause of mortality that we see in the first 56 days of life,” Ballou said. “If a calf gets scours, they’re 7.1 times more likely to die than a calf that doesn’t get scours.”

By day 60, only about 75% of calves that had experienced diarrhea were still alive, meaning one in four died during the pre-weaning period. Calves that avoided scours maintained near-complete survival.

Early disease carries lasting performance penalties

Beyond mortality, Ballou stressed that scours leaves a lasting imprint on growth performance, especially for beef-on-dairy calves.

“Do those calves wean as well?” Ballou asked. “The answer is no.”

Data from the Texas Tech study showed that calves experiencing diarrhea consumed less calf starter and gained less weight prior to weaning. But the magnitude of the effect differed sharply by calf type.

“At 56 days of life, beef-on-dairy calves that got scours weighed 21.2 pounds less than beef-on-dairy calves that didn’t get scours,” Ballou said. “That’s huge.”

By comparison, Holstein calves experiencing scours were approximately 8 lbs. lighter at weaning, certainly a meaningful loss, but far less severe than what was observed in beef-on-dairy calves.

“That was one of the unique things in this dataset,” Ballou said. “Beef-on-dairy calves are more susceptible to the negative impacts of diarrhea on average daily gain.”

The pattern reversed when respiratory disease was examined. Holstein calves that developed BRD were 11.6 lbs. lighter at weaning, while beef-on-dairy calves lost only about 2 lbs.

“So, it was the exact opposite,” Ballou said. “Beef-on-dairy calves were more impacted by scours, where Holsteins were more impacted by bovine respiratory disease.”

Starter intake emerges as a critical driver

A recurring theme throughout Ballou’s presentation was the central role of early calf starter intake in determining weaning success.

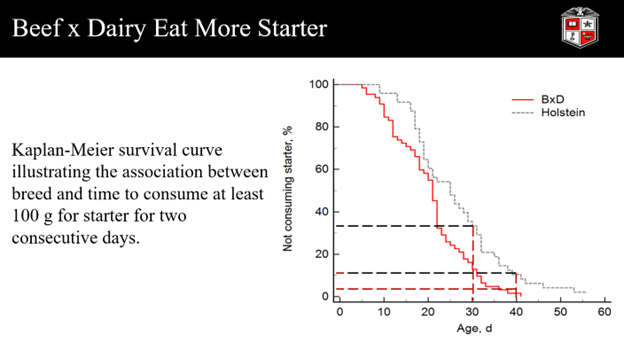

Using intake curves from the same study, Ballou showed that beef-on-dairy calves began consuming starter earlier than Holstein calves, which is an observation consistent with industry experience. However, the data also revealed management risks when calves are weaned before adequate starter intake is established.

“At 30 days, about 30% of the Holstein calves aren’t consuming 0.25 lb. of calf starter,” Ballou said. “We’re going to start weaning these calves maybe at 42 days. What’s going to happen to those calves that aren’t consuming calf starter when we start trying to wean them? Are they going to do well? Most likely not.”

Even among beef-on-dairy calves, roughly 10% were not consuming at least 0.25 lb. starter by 30 days of age.

Ballou cautioned that group-based management often overlooks this vulnerable minority of calves, leading to poor transitions off milk.

“We want to manage as much as a group,” he said. “But we do have to do some individual management, and sorting can be an important strategy.”

Milk alone is not the solution

Ballou addressed ongoing debates around milk feeding intensity, emphasizing that simply feeding more milk does not solve underlying management problems.

“If you have a problem and you throw more milk at it, it’s probably not going to fix it,” he said. “If you have problems and you take milk away, it’s probably not going to fix it either.”

Instead, Ballou urged producers to focus on starter intake management, hygiene and consistency.

“How often are you cleaning buckets?” he asked. “How are you making that calf starter? Is it in a form that is palatable to the calf?”

He noted that starter intake as early as 21 days of age can reliably predict weaning weights under restricted milk programs.

“If I measure a calf’s intake at 21 days, I can accurately predict what that calf’s going to weigh at 60 days,” Ballou said. “If I do a really bad job managing my calf starter, guess what? I have to feed them more milk to get them to gain.”

Disease reduces intake, intake drives gain

Data from the Texas Tech study reinforced a simple but critical point: sick calves eat less, and calves that eat less gain less.

“Calves that get diarrhea don’t eat as much starter,” Ballou said. “By default, they don’t gain as well.”

The same pattern held for respiratory disease, although the impact on weight gain differed by calf type. Ballou emphasized that the interaction between disease and nutrition magnifies losses during the pre-weaning period.

“It’s hard to get anything with that magnitude of an effect,” he said, referring to the 21-pound weaning weight penalty associated with scours in beef-on-dairy calves.

Nutrition, environment and comfort interact

Ballou reviewed literature data comparing the relative impacts of milk feeding rates, starter intake, colostrum management and environmental conditions on weaning weight. Across studies, increased starter intake consistently delivered some of the largest gains.

“For every 100 grams (about 0.25 lb.) increase in starter intake at 28 days, we saw about a five-pound improvement in weaning weight,” he said.

Environmental factors proved equally powerful. Bedding alone accounted for a roughly 22-lb. improvement in weaning weight when calves were provided straw or shavings compared with no bedding.

“Calf comfort matters,” Ballou said. “It’s probably the most important thing.”

He summarized his current philosophy bluntly: “I would rather spend $3 more on calf comfort than $3 more on another vaccine.”

Ballou stressed that nutrition, health and environment are not independent factors.

“They’re not mutually exclusive,” he said. “Calf comfort is going to improve calf health. They interact with each other.”

Gut health and bioactive nutrition

Turning to gut health strategies, Ballou highlighted nutrition as an attractive intervention point because it delivers functional components directly to the gastrointestinal tract.

“There’s a lot of different ways we can improve gut health,” he said. “Nutrition is supplying things directly to the gastrointestinal tract.”

He emphasized the role of colostrum and transition milk beyond immunoglobulins.

“Colostrum has a lot of bioactives,” Ballou said. “A lot of those things are actually growth hormones.”

Citing research showing improved intestinal development in calves fed transition milk for several days, Ballou explained that villi length and absorptive capacity was substantially greater when transition milk feeding was extended.

“Those tissues are healthier when we extended transition milk feeding,” he said.

Ballou also described research on binding pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella.

“You can actually see Salmonella binding to the surface,” he said. “Both activated carbon and ceramic particles can bind E. coli and Salmonella really well.”

Electrolytes, hydration and transportation

Ballou addressed electrolyte strategies for hydration, disease management and calf transport.

“If you want to hydrate a calf really quickly, feeding just electrolytes is a good way to get fluids in there fast,” he said.

He cautioned against bicarbonate-based electrolytes, particularly when milk is present in the stomach.

“You want to buffer blood,” Ballou said. “You don’t want to buffer the digestive tract.”

Ballou outlined a specific electrolyte-based transport protocol used at his operations, emphasizing rapid rehydration before and after long hauls.

When preparing to load calves for an overnight transport, calves are fed milk in the morning, an electrolyte around noon, and then another bottle of milk an hour before we load them on the trailer. Calves are loaded on the truck at about 5 pm and are transported overnight. When those calves are unloaded, they immediately receive an electrolyte.

“They haven't eaten in 17 hours, and it feels like you should give them milk, but don’t worry – you will,” he said. “First, they are a little dehydrated so we give them an electrolyte that will be quickly absorbed and then two hours later, I feed a bottle of milk because the electrolyte is only 150 calories. It's not going to make them full only hydrated, then the milk which will stick with them longer.”

Key takeaways for beef-on-dairy systems

Ballou closed by reiterating that diarrhea remains the most damaging early-life challenge for beef-on-dairy calves – both in terms of survival and growth.

“Diarrhea continues to be a major cause of mortality and severely affects the growth and performance of beef-on-dairy calves,” he said.

He emphasized that nutritional strategies, aggressive hydration protocols and above all calf comfort represent the most effective tools available.

“I really believe that calf comfort has an edge over both nutrition and disease,” Ballou said.

For an industry increasingly dependent on beef-on-dairy calves to supply the beef pipeline, the implications are clear: early management decisions in the hutch can have outsized consequences long before calves ever reach the feedlot.