OpEd: Deportation policies are crippling America’s livestock & meat sector

The real cost of deportation to the livestock industry and its communities

The U.S. livestock and meat sectors are staring down a labor crisis. As federal immigration officials prepare to deport more than one million undocumented workers, meatpackers, dairies, poultry processors and cattle operations are bracing for severe workforce disruption. The impact will not be theoretical. It will show up on the line, in the barn and on the shelf.

The numbers speak for themselves. According to USDA data, undocumented laborers make up 42% of the total U.S. farm workforce. In meat and poultry processing, estimates run as high as 50% of frontline staff. That translates to as many as 270,000 workers who currently handle everything from live animal intake to cutting, trimming, packing and sanitation. Lose those workers and output slows immediately. Some facilities may shut down entirely, causing scarcity and likely increasing prices consumers will have to pay.

Dairies are even more exposed. Cows do not wait. They require milking, feeding and care every day without exception. Over half of US dairy workers are immigrants and a significant portion are undocumented. A large-scale removal of that labor would put animal welfare at risk, cut off milk supply and drain local economies built around dairy infrastructure.

To fill the labor vacuum, the Department of Agriculture is floating a controversial idea. Secretary Brooke Rollins suggested that the 34 million adults currently on Medicaid could be tapped as a domestic labor pool. But the math does not hold up. Only 5.6 million of those recipients are unemployed. Even fewer are physically able or willing to take on rural labor-intensive work under tough conditions. Analysts say that no more than 750,000 individuals in that group could realistically be placed into agricultural jobs. And even that projection assumes major changes in recruitment, training and relocation.

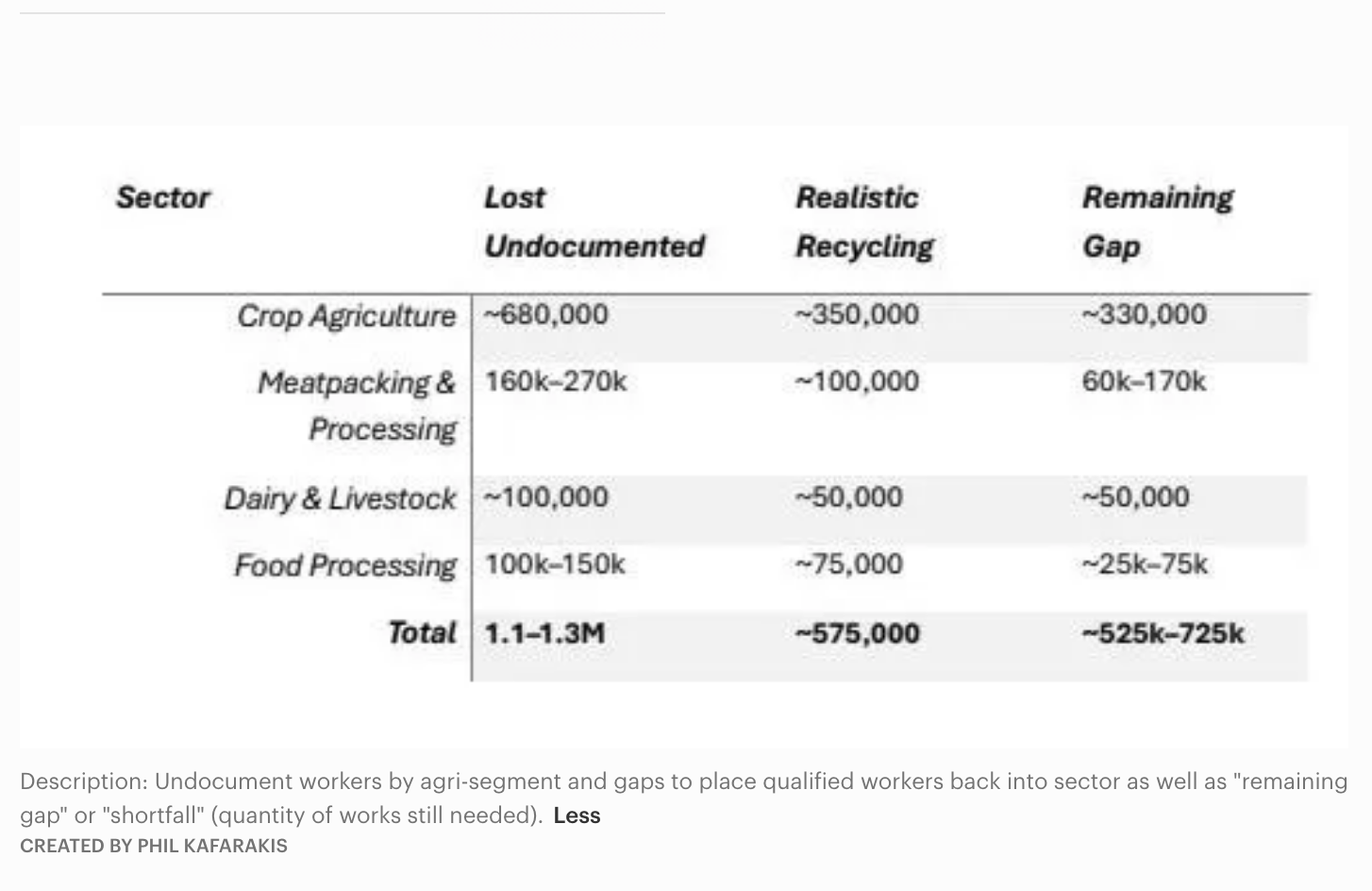

That still leaves a gap of more than half a million positions across the food production ecosystem. In the beef, pork and poultry processing, cattle feedlots and handling, and dairy sectors taken separately, the gap is nearly half of that number.

Current USDA estimates of undocumented labor by sector can be compared to the theoretical number of Medicaid recipients who could plausibly be transitioned into physically demanding agricultural roles, based on unemployment status, geographic proximity, and health suitability.

In the dairy, livestock and meat sectors, a little number-crunching reveals that around 300,000 undocumented workers currently work these jobs; total potential Medicaid replacements account for no more than 115,000. So even under generous assumptions, the US livestock and meat industries face a labor shortfall that could reach nearly 200,000 workers.

This gap is not evenly distributed. Red meat and poultry processing are the most exposed, due to their size, labor intensity, and lack of automation alternatives. Dairy also faces unique risks, given the 24/7 nature of animal care and the impossibility of shutting down operations even temporarily.

These are not office jobs. These are jobs in slaughter plants, in milking parlors, in cold rooms and feedlots. They are physically demanding, often dangerous and almost always located in areas where local unemployment is near zero.

Andrew Mickelsen, a seventh-generation Idaho potato farmer, told WBUR he offers $17 an hour and still cannot get local applicants. Similar stories are common across the livestock supply chain. The labor simply is not there.

Automation continues to be discussed, but its real-world application remains limited. Robotic arms struggle with the variability of animal carcasses. Poultry lines move too fast for machines to consistently match human dexterity. And in dairy, robotic milking requires capital investment many small farms cannot absorb. As Ryan Jacobsen of the Fresno County Farm Bureau put it, a fresh peach still requires a pair of hands. The same is true for much of the meat and dairy sector.

Another proposed fix involves expanding the H-2A visa program. Right now, it applies to seasonal agricultural work, not year-round processing or dairy operations. Even where applicable, the program is tangled in bureaucracy and cannot meet current demand. Without an overhaul, it will not solve this problem.

The business implications are already taking shape. Labor costs are climbing. Production is slowing. Investors are watching capital expenditures tick upward as companies scramble for automation or other stopgaps. At the same time, retailers are bracing for product shortages and higher prices. And in many rural communities, the concern is more fundamental. When a packing plant closes, the ripple effects are immediate. Feedlots lose buyers. Truckers lose routes. Cafes close.

Chobani CEO Hamdi Ulukaya warned at the WSJ Global Food Forum that aggressive immigration policies pose a real threat to the food system. He called for a more realistic view of workforce needs and acknowledged what most processors already know. Without immigrant labor, the U.S. food system cannot function.

Without a rapid policy pivot, the livestock and meat industries will face higher operating costs, tighter labor markets and greater supply volatility. For now, the political rhetoric continues to ignore the basic economics of food production. But on the ground, in the barns and on the lines, the damage is already underway.